Copyright Manuel Lima

A reflection on “Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age” by George Siemens (2004) and “Arc-of-Life Learning; A New Culture of Learning” by Douglas Thomas and John Seely Brown (2011)

“When knowledge…is needed, but not known, the ability to plug into sources to meet the requirements becomes a vital skill” (Siemens, 2004).

George Siemens’ text was, at first, a real pain. Wrestling with unfamiliar and abstract theories of chaos and self-organization, I found myself arriving again and again at dead ends in my understanding. Frustrated and knowing that I needed to actuate my learning by writing this blog post, I turned to the resources at my disposal to try to gain some clarity.

I first tapped into my Personal Learning Network. With the social highlighting and commenting functions of Diigo, I could benefit from the collective knowledge of my peers. Having little personal experience with the principles of “chaos, network, complexity, and self-organization theories,” “other people’s experiences, and hence other people, become the surrogate for knowledge” (Stephenson). Accessing other students’ annotations helped me to zoom in on the concepts of Connectivism that were essential for understanding and gloss over those that were perhaps obscured by an over-reliance on theory and academese. As Siemens reminds us, “the ability to draw distinctions between important and unimportant information is vital.”

Diigo – “Learning and knowledge resting in diversity of opinions”

While the insights of my immediate social learning network were illuminating, I was in search of some clarification straight from the horse’s mouth. By browsing through links on eLearnSpace, the website on which Siemen’s article was posted, I discovered a barrage of texts and presentations that explained the core principles of Connectivism more clearly.

In scrolling aimlessly through Twitter on Friday night, I came across a TED Talk shared by an instructional designer I know only through social media. Presented by infographics expert Manuel Lima, the lecture titled “A Visual History of Human Knowledge” traced the thousand-year history of mapping data using trees and networks. Lima’s exploration of the ways in which we visually represent knowledge turned out to be a perfect scaffold for my understanding of Connectivism, especially in its focus on networks. As Siemens notes, “connections between disparate ideas and fields can create new innovations”, or in this case, new understandings.

Satisfied and somewhat relieved by a breakthrough in understanding, I reflected on how I had arrived to this point and, startled, laughed out loud.

By combining the socially-distributed knowledge of our EDTEC467 class with supporting information found on linked websites and loosely-related ideas discovered through weak social ties, I had demonstrated the exact behaviors that Siemens finds emblematic of Connectivist learning.

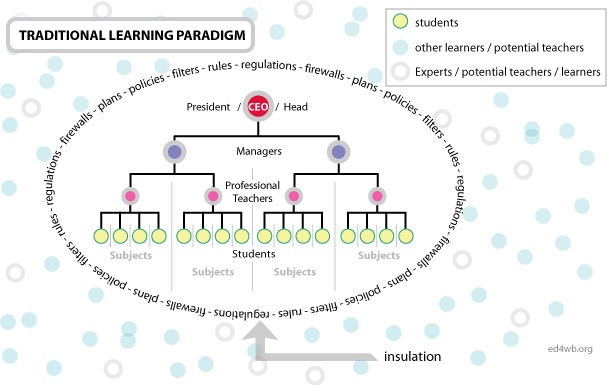

In a networked ecology of learning, we draw on connections near and far to bolster, organize, and enact our understanding. Organizational sources of knowledge that were traditionally at the top of a learning hierarchy – schools and teachers – are now only a few of the infinite nodes in a network of knowledge.

Seeing visual representations of networks was so helpful in my path to understanding Connectivism that I explore this idea in greater depth below, in hopes that it might serve as a resource for others in search of clarity.

Scala Naturae : The Ladder of Nature

The Great Chain of Being (Retorica Christiana, 1579)

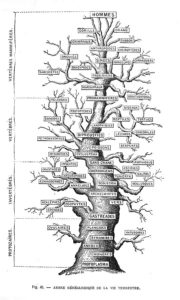

Dividing the world into categories is a basic method the human mind uses to make sense of the world. Robert Gagné, educational psychologist and legend in the field of Instructional Design, identified discrimination as our most basic intellectual skill. Distinguishing and classifying things based on their essential differences is the foundation on which we develop our higher-order intellectual skills: forming concepts, applying rules, and solving problems (Gagné, 1985).

We can see the human impulse to classify even in the earliest reaches of civilization. Dating back to Ancient Greece, the Great Chain of Being (in Latin scala naturae or “ladder of nature”) was one popular ranking system that classified all matter based on a religious hierarchical structure. With God at the helm, the chain progressed downward, putting angels, the moon, kings, commoners, animals, metals and minerals in their places.

While the government structures implicit in this model, with its kings and commoners, changed over the centuries, the hierarchical approach continued to serve as a powerful model for categorization.

The branching structure of a tree, first seen in representations of the Great Chain of Being, became a useful visual metaphor for displaying hierarchy — both for social and knowledge systems. As its applications diversified, the tree map took on a more abstract representation, shedding its visual nods to the natural world and keeping only its underlying branching structure.

In a linear, hierarchical ecology of learning, knowledge and power flow down from teacher to student:

Traditional Learning Paradigm, Copyright ed4wb.org

Still, Siemens argues that as the world progresses, so must our representations of it. The creation of technologies that allow for visible and meaningful connections between people and their embodied knowledge has led to a global ecosystem that is so complex and quickly changing that it can be described as chaotic. The simple tree diagram has become insufficient to represent this kind of complexity. In its place, a new visual metaphor has emerged that highlights the importance of connections in our new ecosystem: the network.

Networks: Nodes and Connections

“The mystery of life begins with the intricate web of interactions, integrating the millions of molecules within each organism . . . Therefore, networks are the prerequisite for describing any complex system” (Barabási, 2002).

Copyright Manuel Lima

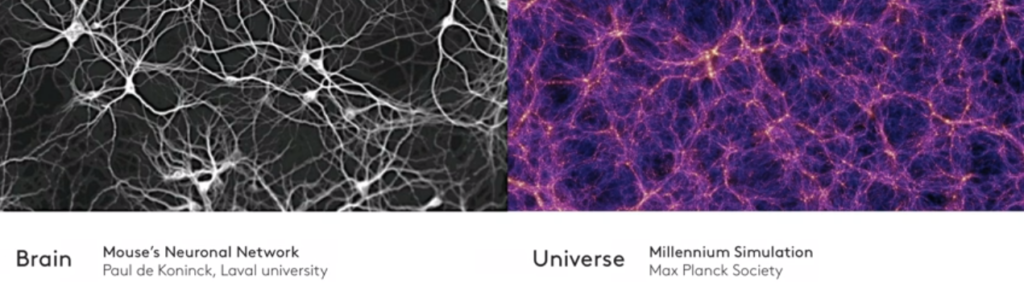

Networks are systems whose structures are characterized by nonlinearity, decentralization, interconnectedness, interdependence, and multiplicity (Lima). They are made of objects, or nodes, and links, or connections, between those objects.

At a most basic and individual level, our bodies and brains are built of networks. Neural networks make up the human brain. Neurons, our brain cells, are the nodes and synapses, the electro-chemical links between neurons, are the connections of the network. Neural networks are not static, but instead change as synapses strengthen and weaken over time in response to activity, a process known as synaptic plasticity.

Zooming out from the networks that make up our internal structures to consider the outside world, we continue to see the pervasiveness of networks. Every day we navigate massively complex systems like transportation, energy, and information systems. Just as in our brain, the connections in these networks strengthen and weaken in response to activity.

We can use the idea of networks to explain social interactions in the digital age, as with this visualization project that shows the relationships linking developers of the Perl coding language. Here, every author is represented by a node. The size of the node represents the number of modules the author has released on CPAN, the standard location for sharing Perl code. Connections between nodes represents times that an author used a module from another author.

Copyright CPAN-Explorer / Manuel Lima

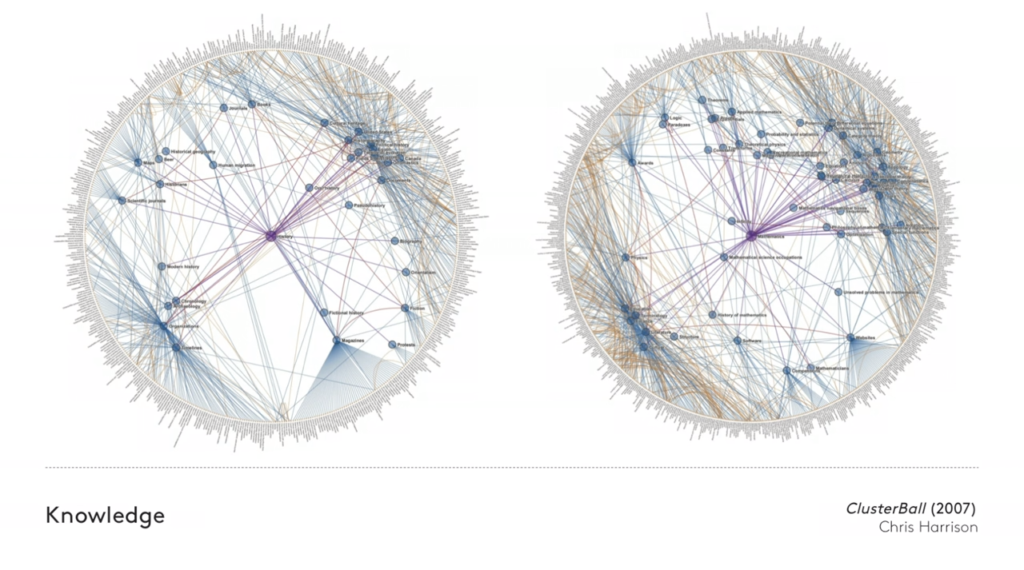

We can also use networks to explain how knowledge is organized and connected by Web 2.0 technologies. This network map shows a series of links between Wikipedia articles:

Copyright Manuel Lima

So, in an ecosystem in which social interactions and knowledge are non-linear, decentralized, and inter-dependent, learning is built by making connections to the vast networked world around us. Teachers who encourage students to cast their nets widely into the web will see that what they catch is worth losing their spot at the top of the learning hierarchy.

Sources

Barabási, Albert-László. Linked: The New Science of Networks. Perseus Books Group, 2002.

Lima, Manuel. “A Visual History of Human Knowledge.” TED Talks. Mar. 2015.

Richardson, William. Traditional Learning Paradigm. Digital image. Education for Well-being. 10 Dec. 2008. <http://www.ed4wb.org/?p=152>.

Siemens, George. “Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age.” Blog post. Elearnspace. 12 Dec. 2004.

Seely Brown, John and Douglas Thomas. “Arc-of-Life Learning.” A New Culture of Learning. CreateSpace Independent Platform, 2001. 17-38.

As we explore the topic of social learning in the digital age together,

I would love to learn from your expertise.

Please share your thoughts by commenting below!

What are some other nodes in the networked learning ecosystem?

How do you encourage your students to practice Connectivism?

In what ways do you engage in “Arc of Life” learning?

Hi Maria!

I liked your focus on Connectivism as a network.

As I was reading, I pictured the web as a giant, human brain that we all “construct” together. The idea set that the technology is learning, is kind of neat if we consider that when many, many people can contribute their own knowledge and experiences to the system, the system itself benefits from all of those contributions. It’s a system (and a network) that “learns” only because we are learning through it. The network becomes an evolving entity thanks to mass interaction. I love that.

Also, looking at your learning paradigm from the instructor to the students, I think some of the great power of social learning and online community is that individuals have the power, even in that little corner of the internet, to climb the ladder themselves. There is a lot more power given to the individual in these online communities… the power to grow, the power to learn, the power to lead, the power to become significant in that moment. It’s interesting to think of an online learning ecology as the same model except people can migrate between the levels constantly, its self driven and fueled by motivation and choice.

Genevieve, thanks for your comment! I think your point about the power afforded to individuals to move into central, leading roles is really key. The online learning ecology does seem to offer greater opportunities for cognitive apprenticeship than most traditional classroom structures do. Learners can move along trajectories of influence with increasing legitimate peripheral participation.

I’m interested in finding examples of classroom environments that allow for students’ roles to change as they gain “the power to lead, the power to become significant.” Seeing a student move from a “lurking” position to that of a peer tutor can be a way to make their learning visible and meaningful. Do you or your school incorporate any of these practices?

Not yet, but I’m working on developing that sort of visible, meaningful learning via Schoology and online assignments and discussions. I’m interested in seeing if creating a culture for valuing asking and answering questions will be enough of a motivator to make a change in the way that students engage with the material in my class.

We’ll see! Once I get things rolling in my classroom with these ideas, I’ll be sure to blog about it and ask for everyone’s input!

Maria,

Your effective use of images and photos in your posts is very helpful to me. I am a largely visual learner. You appear to be experienced with blogging and blog design. Would you be interested in passing on a few tips, especially for how you are sharing images. I am concerned about copyright and giving proper credit in my posts. What is the protocol for this? Where do you find your images? Sorry for all the questions, but I am attempting to use the Connectivism theory to link up with my PLN.

Maria,

I’m intrigued by your voice and opinions in diigo so I decided to read your posts even though you are not in my group. And I’m not disappointed! hah!

Ok, so 1st off, on something a bit mundane and basic, your blogs are visually very appealing. I’m with Heidi on this. I wanna know more. I know how to insert images, but don’t know how to position them (except for the default position). I don’t know how to insert image so the text flows around it. Also I see the green box “light-bulb” is nice. Another example is scrolling over an image as we scroll up/down.

maura

Thanks so much, Heidi and Maura! I also find visual representations to be really helpful in breaking down some of the more complex ideas we’re tackling.

In general, I try to only use copyright free stock photos to avoid having to worry about citations. This website has a list of sources under the “Where to Find High Quality, Beautiful Images” header that I found useful: http://bit.ly/1FgbbwE

This site is great for photos of people using technology. It’s mostly geared toward startup culture, but some work for education as well: http://startupstockphotos.com/

For this blog post, I was unable to find stock photos that represented real-world examples of network, so I tried to find the copyright and attribution requirements for the images that I used and cite them accordingly.

Maura: When you’re editing a post and you click on the “Add Media” button, you’re taken to a page where you can select the photo you want to use. On the right side of the page, you can see a sidebar titled “Attachment Details”. If you scroll down to the bottom of that sidebar, you should see a section titled “Attachment Display Settings”. There, you can select the alignment you want for your photo (left, center, right, or none). Using that setting, the text will automatically flow around the image.

The pop-up boxes and parallax image scrolling are neat features of the theme I chose for my blog: Divi. Divi is a drag-and-drop interface, which makes it easy to add interesting visual effects to a blog. It can take a little tinkering to get used to, but it is a lot of fun to customize. You can see a demo of the theme and reference the set up documentation here if you’d like to give it a try: http://sites.psu.edu/insites/2015/07/07/updates-divi-theme/

I was interested by your comment about “clarification straight from the horse’s mouth.” I believe as we move forward in a technology oriented learning environment, it is important that we fact check as much as possible. I am not sure of the best way to do this. I do know that it is becoming increasingly easy to create websites, twitter accounts, and blogs that allow us to easily share information. It is also easy to share incorrect information. What do you think are best practices to fact check in an environment where it is so easy to disseminate false information?

Ben, that’s a great question. I was raised in a schooling environment in which Truth was whatever my teachers said. Now that we’re working in a learning ecology where knowledge is socially distributed, I have to resist my urge to dismiss conversation and questioning as distractions in a search for the “facts”. I’m coming to see increasingly that for many of these ideas, there is no one right way of understanding.

That said, one way that I try to fact check is to do a Google search to see if that particular information is cited in reputable sources. I generally trust .edu and .gov sites, as well as major newspapers, relying on their internal fact-checking departments to do the work for me. There may be some other technology-supported practices for fact checking that I’m not aware of. What are the strategies that you use?

I was frustrated reading Siemens’s connectivism. You provided more relevant sources in Diigo and those helped me understand better what he was talking about. I have a little extra time this week so I decided to take a peek at your blog. Wow I think you manage to surpass all those other sources. The visuals and your insight and reflection took me a step ahead and I can a bit more confidently now say yeah ok I kinda get it… well, at least I hope so ☺

My question to you, as was posed also by Professor Sharma, do you think that connectivism is a new learning theory? You said “In a networked ecology of learning…”, does it mean you think connectivism is maybe a new ecology of learning but not really a new theory?

I had to look up the meaning of the words ecology and theory because I’m not 100% sure of the meaning. dictionary.com defines

(human) Ecology: the branch of sociology concerned with the spacing and interdependence of people and institutions.)

Theory (many definitions, I take this one as particularly relevant in this context): a particular conception or view of something to be done or of the method of doing it; a system of rules or principles:

I’m struggling in accepting his proposal that it is a new learning theory (Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age). I accept it more as a new learning ecology.

I just feel that we as human beings have always had to make connections ever since birth. For example how babies learn language and how adults learn a foreign language, whether formal, or informal, or implicit (Bransford et al., 2006, Learning theories and education: Toward a decade of synergy). Even before the invention of the web and internet, we have always had multiple media to navigate around (newspapers, textbooks, formal conversations / lectures, informal conversations / with peers, microfiche in libraries, etc.). The media may have changed (the worldwide web!); the interactions may have changed (complicated, dynamic, fluid networks), but how the brain learns and thus affecting learning theories haven’t changed.

Maura, thanks for your kind words. I think you’re spot-on in presenting Connectivism as a learning ecology instead of a learning theory, and not a particularly new one at that.

You’re right that even in the pre-web world, we have always made connections to people and knowledge sources in doing the work of learning. I think the main change that the Internet has brought about to the learning ecology is that it has removed hierarchical, power-based barriers to knowledge sharing. Democratizing publishing allows more people, not only experts, to create nodes — units of information — and share them. Thus growing the network we have available to support our learning.

Hey Maria,

I really like your raising of the Scala Naturae. It’s a great reference point for learning/knowledge in this context. It is compartmentalized, structured and hierarchical and an anti-thesis of what Siemens is putting forth.

You raise Siemen’s argument that “as the world progresses, so must our representations of it.” And say “the simple tree diagram has become insufficient to represent this kind of complexity.” I’m curious to know if you agree or disagree with this view/position?

Sean

Hey Sean, thanks for reading and commenting. The Scala Naturae does work as a nice foil to Siemens’ argument.

That said, while the network framework is useful for interpreting our world’s increasingly distributed and connected systems of social interaction and knowledge, I think the hierarchical structure of the tree map maintains an important role in learning. Hierarchical categorization might be most useful in helping us to break down and understand individual chunks of information. So it’s more of a tool than a representation of a system.

When learning something new, I do find myself moving through Gagné’s hierarchy — classifying, forming concepts, applying rules, and solving problems — in that increasing order. But that might be a cognitivist way of thinking about knowledge, relying too much on internal mental calculations.

I’m curious to know your thoughts on this! Do you think that hierarchical categorization can have a role in a networked ecology of learning?

Hey Maria,

My simple response to your question of what my thoughts are on this are nicely summarized in your first paragraph. 🙂 My lies simple answer is…

I think it’s great you use hierarchical taxonomy (if that isn’t redundant) to learn. I think is has value and continued relevance in today’s world, education and the process of learning.

While reading his and Seely Brown’s work I found myself saying, ” Yes. Yes. Yes. No!” I’ll explain what I mean by that in a moment.

like you, as I read the paper I found myself saying, “Huh? I’m confused.” So I turned to other sources to try and understand what he was saying.

I watched three presentations he gave on Connectivism through YouTube. As I listened to him I would think to myself, “Yes. I agree with that point. Yes. I agree with that point too.” But then he will draw a conclusion and I would say out loud in exasperation, “No! I disagree. How can you say that?”

So I thought, “Clearly I am missing something here. This guy is an expert. It must be that I don’t understand what he is saying.” So I watched Stephen Downes presentations (he’s a colleague of Siemens) hoping a different person’s explanation would help clear things up.

No luck there either. I continued to agree with some of their premises but not their conclusions.

In my sophomoric interpretation of their position I think they are wrong. Learning isn’t a purely connected and social. It can be a very solitary process.

You ask, ” Do you think that hierarchical categorization can have a role in networked ecology of learning?”

I think networked learning and hierarchy are both each a subset of learning.

Sean

My lies simple answer is… = My LESS simple answer is…

(Stupid keyboard…)