“There never was a trumpet playing in New Orleans that had the fire that Joe Oliver had. Fire - that's the life of music, that's the way it should be.”

Louis Armstrong

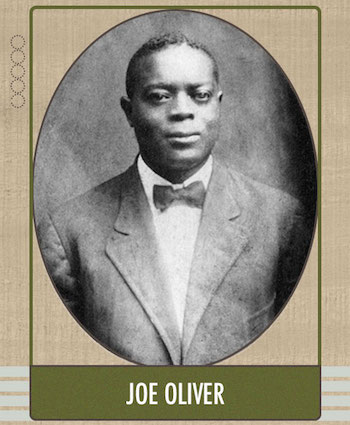

The Man

King Oliver is said to have begun music as a trombonist, and from about 1907 he played in brass bands, dance bands, and in various small groups in New Orleans bars and cabarets. In 1918 he moved to Chicago (at which time he may have acquired his nickname), and in 1920 he began to lead his own band. After taking it to California (chiefly San Francisco and Oakland) in 1921, he returned to Chicago and, with some of the same musicians, started an engagement at Lincoln Gardens as King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band (June 1922). This group was joined a month later by the 22-year-old Louis Armstrong as second cornetist. With two cornets (Oliver and Armstrong), clarinet (Johnny Dodds), trombone (Honore Dutrey), piano (Lil Hardin), drums (Baby Dodds), and double bass and banjo (Bill Johnson), Oliver began recording in April 1923. Many young white jazz musicians had the opportunity to hear him then, either on recordings or live at Lincoln Gardens.

By late 1924, after a tour of the Midwest and Pennsylvania, the completely reorganized band included two or three saxophones, and played in Chicago as the Dixie Syncopators (February 1925 to March 1927); the most distinguished of the saxophonists who played with this band were Barney Bigard and Albert Nicholas. Soon after a brief but successful engagement at the Savoy Ballroom in New York (from May 1927) the members began to disperse and by autumn the group had disbanded, but Oliver stayed in New York, recording frequently with ad hoc orchestras. From 1930 to 1936 he toured widely, chiefly in the Midwest and upper South, with various ten to 12 piece bands; he himself seldom performed during this period, and he made no further recordings after April 1931. He spent the final months of his life in Savannah retired from music.

The Music

Oliver is generally considered one of the most important musicians in the New Orleans style. Like other early New Orleans cornetists, he played in a relatively four square rhythm and clipped melodic style (contrasting with the deliberate irregularity of the younger Armstrong and his imitators) and had a repertory of expressive deviations of rhythm and pitch, some verging on theatrical novelty effects and others derived from blues vocal style. He frequently used timbre modifiers of various sorts, and was especially renowned for his wa-wa effects, as in his famous three-chorus solo on Dipper Mouth Blues (1923), which was learned by rote by many trumpeters of the 1920s and 1930s and which, as Sugar Foot Stomp, became a jazz standard. As a soloist he may best be heard in a number of blues accompaniments, notably with Sippie Wallace.

In contrast to his near-contemporaries Freddie Keppard and Bunk Johnson, Oliver integrated his playing superbly with his ensemble, and was an excellent leader; the Creole Jazz Band may have been successful largely because of the discipline he imposed on his musicians. Indeed, of the earlier New Orleans cornetists, only Oliver was extensively recorded in the 1920s with an outstanding ensemble, and the revival of New Orleans style, which began shortly after his death, owed much to the rediscovery of his early three dozen Creole Band recordings, which were internationally known by the 1940s. After 1924 the quality of his recordings declined, partly because of recurrent tooth and gum ailments and partly because his style was at odds with that of his younger sidemen; but with a good orchestra he was capable of coherent and energetic playing even as late as 1930. Almost all of his recorded performances have been reissued.

The Legacy

Oliver's influence is difficult to assess: his playing during his New Orleans period (his best years, according to Souchon) was not recorded, and by 1925 his style had largely been superseded by Armstrong's. He had an obvious formative impact on Ellington's sideman Bubber Miley, and perhaps on such white musicians as Muggsy Spanier; his mute tricks were copied by Johnny Dunn; and trumpeters such as Natty Dominique and Tommy Ladnier, who remained apart from Armstrong's influence, may have derived their styles in part from Oliver. The extent of Oliver's influence on Armstrong himself, though clearly audible and significant, has yet to be examined properly. Oliver is credited with many melodies on record labels and in copyright registrations; it is not known how many of these he actually composed.